Editor's Note: You've seen the “American Iron” feature. Chris Maida, the editor, asked us to reshoot it, but we kept the original shots near the Wilmington, Califa, Port of Los Angeles rail road tracks. Just happened that a train rolled past in the middle of the shoot. Enjoy.–Bandit

I just did the Old School bit and rode this bike to Sturgis on our Bikernet.com 2005 run from the West Coast.

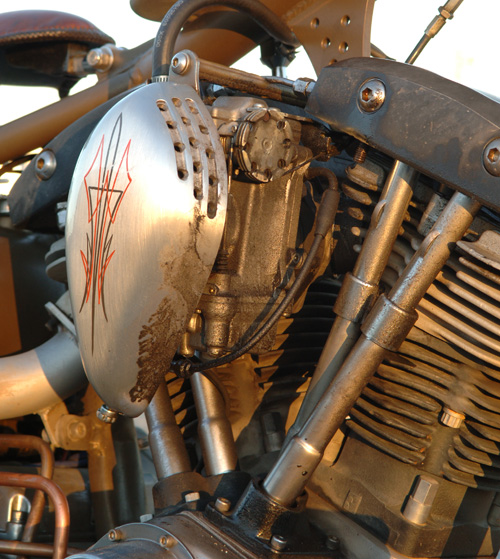

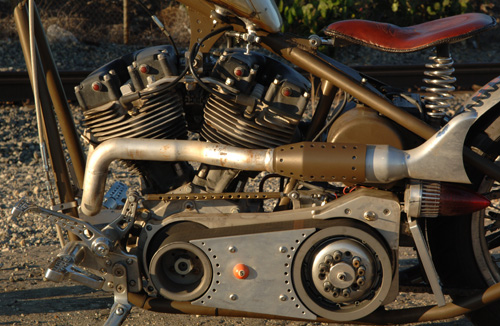

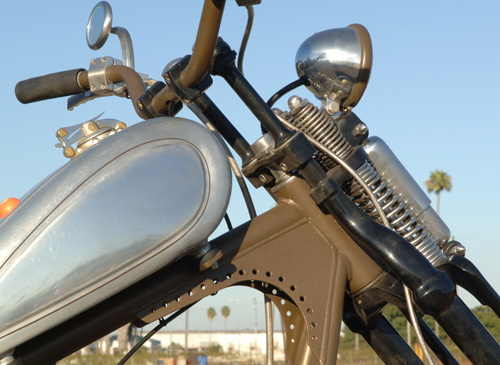

I cottoned to the pure machine marquee. I didn’t plan to paint it at all, unless absolutely necessary. I wanted to leave most components unblemished metals and incorporate as many iron types (for color) into the mix as possible. I wanted this mess to contain brass, copper, aluminum, steel, and stainless. Of course the steel corrosion dilemma dictated that we use some powder coating for a protective seal. The front end came in black to avoid chrome, so I supplemented the bike with a few additional black pieces, but the frame and some others were powdered to mimic a copper patina. Some aluminum parts were clear coated to prevent complete dulling and afford an acceptable pin striping surface. Some brushwork was applied.

It started with a Shovel engine that a brother gave me with a title. I loaned him a bike when he was down. Due to family illness he was forced to sell everything. There’s nothing better than an engine with a title. I took it from there and ordered a Paughco classic frame to fit me and handle like a midnight dream. Too many choppers today look good but don’t handle worth a damn. I wanted a bike to fit, handle well on freeways, yet be light in city traffic and parking lots. I spoke to Ron Paugh at Paughco and they built me a 4-inch up, 3-inch out, 35-degree raked rigid, wide enough to handle a 180 tire.

I don’t care for wide tire, fat-assed, beachball monsters. I decided to set my limit at 180 and run an O-ring chain for the traditional look. I stuck with a Paughco front end to top off the chassis. It’s one of their new tapered leg springers, 9-inches over with three degrees of rake in the trees. It worked out to be almost 5 inches of trail and handled as light as a dirt bike.

The engine had early stock heads, House of Horsepower cases and was a 105-inch stroker, too much for a rigid chassis. I wanted this bike to last, be a beater, but not be a dog. I contacted friends at S&S and they suggested 93 inches of street power for a balanced, reliable drive train. The stroke was reduced to 4.5 inch with 3 5/8 inch bore. The bike is fast but not a vibrating monster. I also spoke to Lee Chaffin at Mikuni and he suggested a 42mm, flat slide, Mikuni carb. “It will give you sharp throttle response,” he said. If I planned to run the Shovel on the salt flats he would have suggested a 45 mm venturi.

I have a couple of codes when it comes to building choppers. I like to keep them as simple as possible. On the other hand I like an oil cooler and filter to keep the drive train alive. I came across a system that bolted to the front motormount and doubled as a cooler while holding a spin-on filter (Rohm billet oil cooler mount). It was perfect. Other chopper codes include having enough taillight to prevent being run-over and enough gas to take you 100 miles before you hit reserve, or you’re looking for gas stations constantly. In this case I nearly broke the code a couple of times.

The Sportster gas tank originated on the verge of being beneath the acceptable fuel capacity, 1.75 gallons. It was an old Aluminum XR 750 race tank that we heavily modified. Get this: Some aluminum tanks are against the code, they’re too weak, notorious leakers. I broke the unwritten rule because it was a factory tank—cool right? Not so. “They broke during flat track races,” Berry Wardlaw, the Boss of Accurate Engineering, said at dinner in Deadwood, South Dakota, after I welded it twice on the way to Sturgis. “They ain’t worth the powder to blow ‘em to hell.”

I put more work into that tank than the Martin Brothers pour into a set of one-off artistic sheet metal. First I added additional rubber mounted bungs to the base of the tank for added support, since I didn’t on the last Sturgis rigid. It broke twice. Because the tank would reside on a severe angle we moved the petcock to the rear, also for more fuel capacity. We drilled the tunnel and welded in a plate to allow the entire center section to augment petrol storage. Then I installed a Crime Scene speedster cap for an old school hot rod appearance.

Kent from lucky Devil Metal Works in Houston supported the aluminum theme by hand fabricating an aluminum fender to match the tank, front and rear. We scrapped the front job.

Back to the code. Remember the taillights, so a semi will at least recognize that it’s a motorcycle under his rip-roaring wheels. This is a tough one for me. I like the minimalist approach, but endeavor for some level of survival. The crew at Eye Candy Custom Cycles (.com) developed this hot looking, side-mount ’59 Cadillac taillight. I thought it was the cat’s paw and that I could mount it to glow through to both sides. I installed it to the BDL inner primary, so close and tight to the frame that no one could see it. I broke the code.

I also grappled with some elements of the wiring, but it worked out fine—that’s another story. I’ve been tinkering with bikes for 30 years, yet learned a tremendous amount with this build.

The bike continued to roll together like a dream with the Kraft Tech oil bag, hard copper oil lines, the Lucky Devil sprung seat and 5-speed Rev Tech Transmission. The wheels were Custom Chrome aluminum rims, stainless spokes and chromed steel hubs. This was the first time I ever used Brembo brakes, no problem and I’ve worked with Joker Machine controls for the last five years.

Let’s focus on mistakes I made, so you won’t make them in the future. The hard lines were cool, but I could have installed rubber hose and been finished in a half hour. Plus, since the Kraft Tech, round oil bag, was rubber mounted and the hard lines solid, the street vibration fucked with them and they cracked. I needed vibration resistant furrels. Let’s stick with the oil bag. It’s cool, solid and bolted right up, but battery choice is critical. There was very little space between the battery terminals and the frame. Ultimately, a Bikernet babe was called to the front, to stitch a rubber protective cushion to prevent shorts. That’s too close for everyday comfort.

I broke in the bike using the Eddie Trotta formula for success, but missed one element, high-speed interstate travel. If I had put a few miles on the bike at 80 mph, which is against the break-in code, of 55 or less, I would have noticed the severe gearing. That’s where I went wrong. I started with a JIMS 6-speed and stock gearing. Then I discovered that the new Starter system from Compufire, that runs off the engine, wouldn’t be available for Sturgis, so I had to punt. I mounted the Dyna coils under the oil tank, which prevented a standard Compu-fire starter from being installed quick. A kicker was the answer. It fit with my hand made exhaust system using modified Samson mufflers, but I was forced to shift back to a Rev Tech 5-Speed transmission, because I needed the kicker. I should have considered a gear change at that point, but didn’t.

So what happened on the 1500-mile trek to the Badlands? The bike ran like a raped ape, strong and true. The handling was superb, everything remained in place except for the bullshit running lights I attempted to use for more visibility. They vibrated, spun, popped the bulbs and tore at the wires running through the fender rails. The ragged glitch in the road was the gearing. I ultimately replaced the running lights with these no-count reflectors and a H-D teardrop turnsignal under the right muffler.

The bike clocked 300 miles before I left town. Another 200 miles down the road toward Arizona, it had the mileage numbers to afford me enough break-in miles to drop the hammer and let her fly. At 90 mph I peeled past big rigs on Interstate10 heading out of the vast Los Angeles plague of concrete and stucco homes reaching dangerously close to the Arizona border. Crossing the state line, into the helmet-free state, I felt relieved to experience 100 degrees in the open desert flying toward Phoenix, another blight of concrete and southwestern architecture. I sensed the buzz in the frame and handlebar grips through Custom Cycle Engineering rubber mounted risers. The Shovel was over-revving and I needed that 6th gear release from extensive vibration, but I kept pushing for the love of speed, a light 520-pound, 93-inch chopper can deliver. She sliced the open road like a high-speed rotary knife through French bread.

I was beginning to buzz my feet off the Joker Machine pegs and adjusted them at the next stop. Rubber inserts on rigid pegs are mandatory, but I flaunted that rule with impunity. Just 60 miles out of Phoenix with the temps cresting 104 degrees and our group, of a half dozen, barreling along at over 90, the Sturgis Shovel quit, pure dead in the fast lane. I reached for the plug wires, then the ignition key that hovered less than a ½-inch from the whirling BDL belt drive. Better not go there, I thought as I signaled to lean right into the slow lane then onto the rough texture of the emergency lane where my baby came to a stop. That’s when I noticed the terrible, over-flowing gas leak at the back of the tank, all over the rear head.

As if the devil knew, one more mile and I would burst into flames in the middle of the searing desert. He flipped my ignition off. I never found an electrical problem or mechanical woe. She turned herself off because the vibration had taken its toll on the aluminum tank.

The next morning I was back on the road after Nick and Charlie at Custom Performance, (Turbo builders for Harleys, in Phoenix), had my tank rewelded and Nick recommended larger, softer rubber mounts. We were back on the road, where I took care of the beast for the rest of the run to Sturgis (kept my speed down), or until I could change the gearing. As it turned out, as I pulled into Deadwood, gas dripped onto that rear plug again. Bad news. There are codes and builders who know which ones can be broken—none. You can check the entire Sturgis Shovel Project build in our Bikernet Tech Department. The tank was repaired in Rapid City, but just two weeks ago I was forced to have it welded for the third time in Los Angeles. When will I learn?

Ride Forever,

–Bandit

Owner: K. Randall “Bandit” Ball

Home: Wilmington, California

Builder: Bikernet.com

Year/model: 1956 Sturgis Shovel

Time to Build: 9 months

Color: Shit brown

Engine/Transmission

Year/Model: 2005 S&S

Builder: Richard Kransler, Phil’s Speed Shop, and S&S

Displacement: 93 inches

Cases: House of Horsepower

Flywheels: S&S side-winder

Balancing: S&S, 1300 Bob weight

Connecting rods: S&S

Cylinders: S&S with longer skirts

Pistons: S&S forged, 8.2:1 compression

Heads: 1966 Shovelhead by Phil’s Speed

Cam: S&S

Valves: Black Diamond

Rockers: S&S rollers

Lifters: Custom Chrome

Pushrods: Custom Chrome

Carb: 42 mm Mikuni

Air Cleaner: Fantasy in Iron

Exhaust: Bandit and Samson

Ignition: Compu-fire, single fire

Charging: Compu-fire

Oil Pump: S&S

Transmission

Year/model: 2005 Rev Tech, 5-speed with kicker

Case: Rev Tech

Gears: Rev Tech

Clutch: BDL

Primary Drive: BDL open belt

Kick Starter: Rev Tech

Chassis

Frame: Paughco Chopper

Rake: 35 degrees

Stretch: 3-out, 4-up

Front Forks: Paughco tapered-leg springer

Swingarm: none

Rear shocks: nope

Front Wheel: 21-inch Custom Chrome

Rear Wheel: 18-inch Custom Chrome

Front Brake: Brembo Caliper and Springer Bracket

Rear Brake: Brembo Caliper and Softail Bracket

Front Tire: 21 Avon

Rear Tire: 18/180 Avon Venom

Rear Fender: Kent Weeks

Fender struts: Bandit

Headlight: Custom Chrome

Taillight: Eye Candy Custom Cycles

Fuel Tank: Aluminum 750 XR

Oil Tank: Kraft Tech

Handlebars: Custom Chrome narrowed

Risers: Custom Cycle Engineering dog bones

Seat: Lucky Devil Metal Works

License Bracket: Eye Candy Custom Cycles

Handlebar controls: Joker Machine

Foot Controls: Joker Machine